Z7_89C21A40L06460A6P4572G3JN0

Inglés UdeA - Cabezote - WCV(JSR 286)

Inglés UdeA - Cabezote - WCV(JSR 286)

Z7_NQ5E12C0L8BI6063J9FRJC1MV4

Signpost

Signpost

Portal U de A

Z7_89C21A40L06460A6P4572G3JQ1

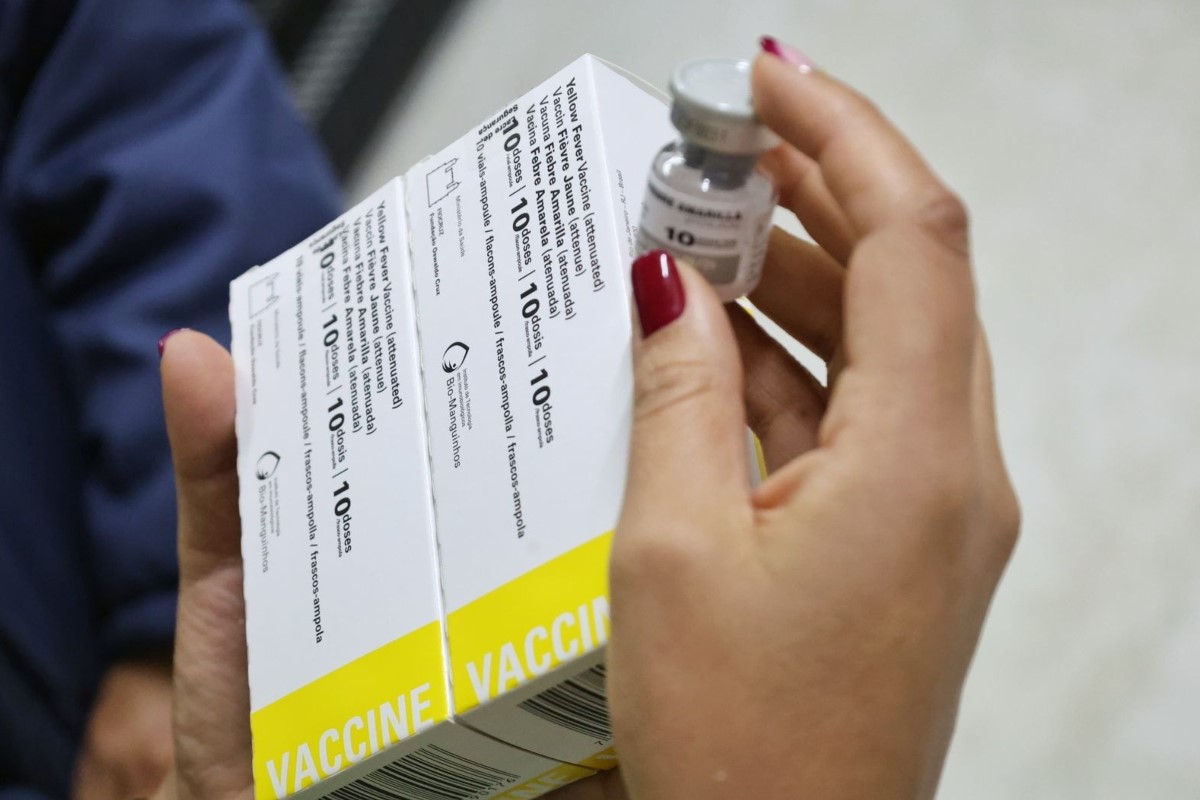

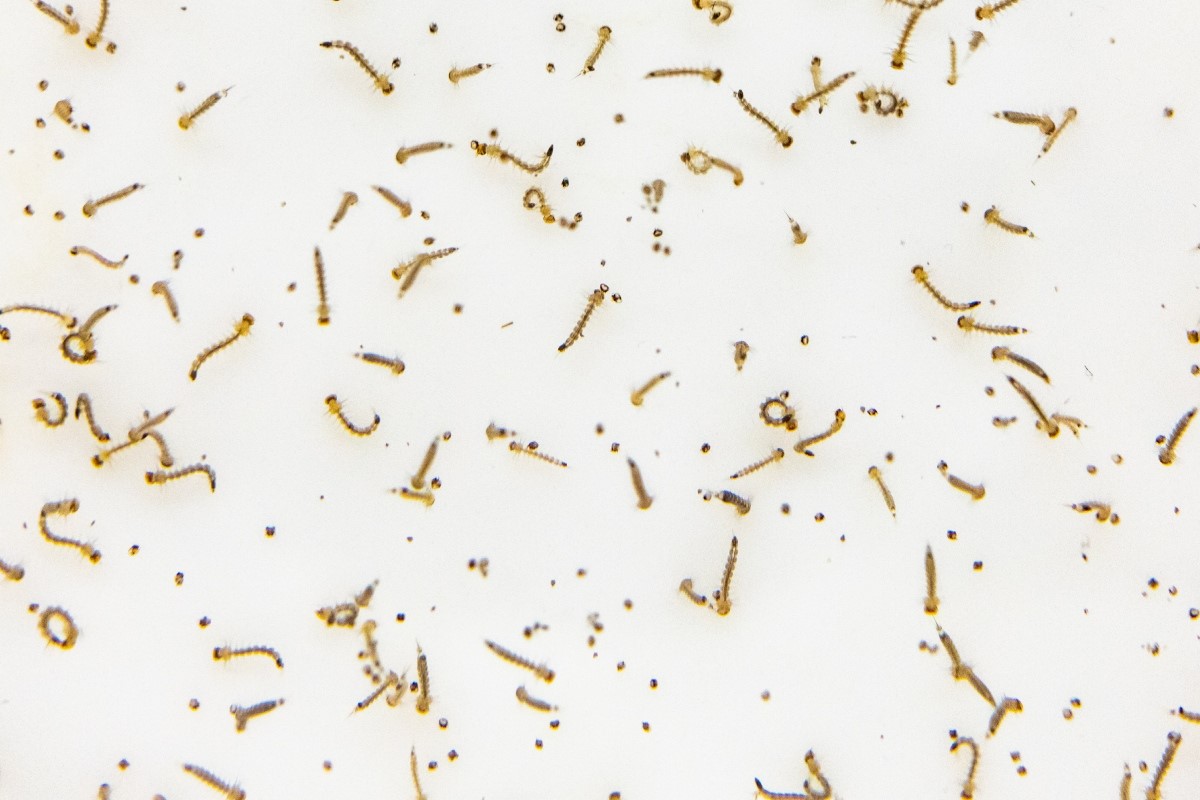

Disease Outbreaks: between early warnings and rapid response

Disease Outbreaks: between early warnings and rapid response

Z7_89C21A40L06460A6P4572G3JQ3

Portal U de A - Redes Sociales - WCV(JSR 286)

Portal U de A - Redes Sociales - WCV(JSR 286)

Z7_89C21A40L0SI60A65EKGKV1K57